Ask no questions, hear no evil

England’s largest examination board pulls its history textbook from circulation after a tweet from a youth worker

I am yet to speak to anyone who followed this story from the end of October, which really, really irritated me. It is very easy to dismiss as a storm in a teacup; it almost begs one to roll one’s eyes, but I cannot shake the feeling that these are the early indications that we are (a) going mad, and (b) foisting our madness upon our children.

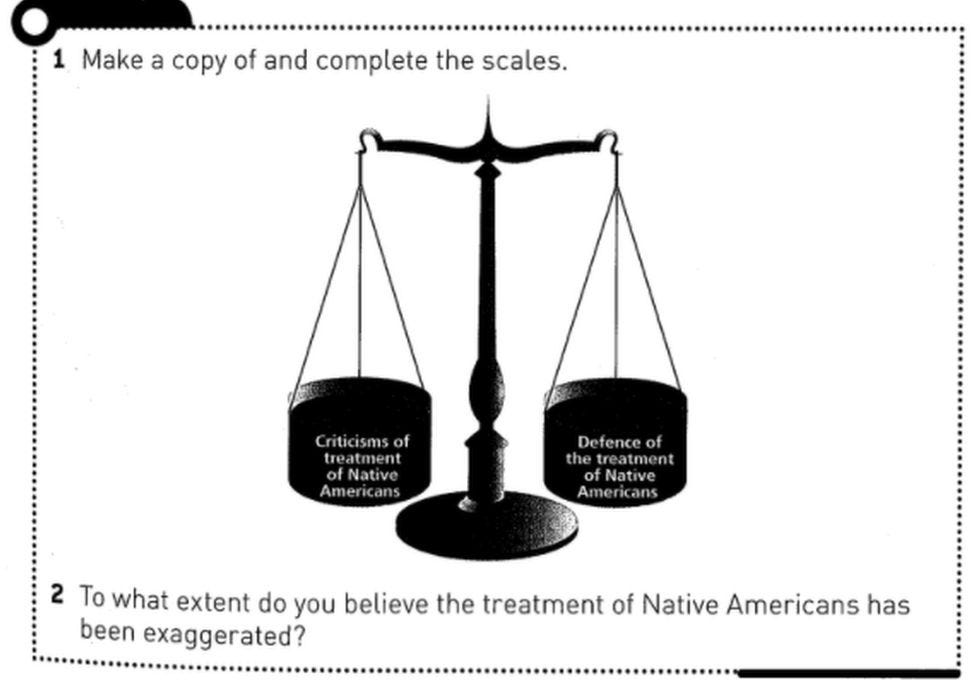

The offending exercise:

The tweet, from a history mentor at Durham Sixth Form Centre:

“Actually horrified”, by a provocative question in a history textbook? The appropriate responses to such a tweet are disbelief and dismay.

Are you “actually horrified”, Hannah? If I were to ask of you, ‘make a case against legalised abortion’, or ‘detail a positive legacy of the British empire’, or ‘to what extent did the trans-Atlantic slave trade rely upon local African slavers?’ — would you be horrified, mortified? Indignant at the posing of the question, offended by the sound? Would you not be able to articulate an argument that you do not believe in, to inhabit a position that you find distasteful? A pity that the bar for ‘horror’ has been lain so low.

Hannah’s tweet is not, I think, particularly serious; the word ‘actually’ betrays her. We often use ‘actually’, ‘literally’, ‘absolutely’ as dramatic little entrees to our dubious exaggerations. I was ‘literally devastated’ when my team lost. My life has been ‘absolutely derailed’ by this latest setback at work. I am ‘actually horrified’ that you would ask me that — I’m fine, really, but let’s see how you react to my outburst…

Hannah is probably not kept awake at night by the thought of this question, but she felt the need to signal her intense, virtuous displeasure at having read it. We make such emphases to elicit reactions, and Hannah got hers:

Remarkable. No-one tell Lois about Mein Kampf. Disturbing numbers of on-side replies (thankfully, almost half are against) allege the question to be asking students to justify genocide:

This sort would eagerly render my questions to Hannah as solicitations for the justification of patriarchy, empire, colonialism, or slavery — so as to dodge the complexity that they consider taboo. Hold up your hands and recite, ‘genocide is, like, seriously bad.’ ‘Was it genocide?’ is considered sacrilege.

These are the fake, worthless cries of passionate fools. You win nothing and no-one by vacating reality. Even if we agree upon the word ‘genocide’ here (a debate for real historians), the question at hand is obviously not asking history students for its justification. This is like dismissing an academic consideration of rare vaccine side-effects as justification for the entire anti-vax movement. The world is not that simple, and these Manichaean games are just fashionable dishonesty.

Now, Twitter is not real life, as the sane know. We need not take such performances seriously, no matter their gratuitous misuse of words like ‘literally’. But the swift, belly-up response of the examiner, AQA, would suggest that they are perhaps not quite sane.

After no more than five likes and five retweets for Hannah’s little Declaration of Indignation, AQA responded that the exercise “doesn't match our commitment to equality, diversity and inclusion and should never have made it through our process for approving textbooks”.

Tweeting within five minutes of one another, the publishers quickly pulled the book from circulation at the examiners’ request, and the examiners commit to be “working together with publishers to ensure that new and updated editions of AQA-approved textbooks meet our commitment to EDI (equity, diversity and inclusion).”

This is a grave mistake. First, it sets a precedent. The content of a nationally accredited A-level history syllabus is no longer the sole remit of a nationally accredited examination board, but also of the general public, and whomever amongst them can muster a playground mandate of a few hundred via the like button (not that AQA waited for more than 10 interactions with the post).

Next will come the biology textbooks, wherein someone will find an offensive sentence regarding the realities of biological sex. Gender ‘activists’ — little could be further from real activism than this textbook malark — can probably smell blood already, with AQA signalling that their educational enterprise is subservient to the cause of EDI. Where will the buck stop when non-binary gender is not enough, and the binary nature of sex dictated by gametes (spermatozoa and ova) is called into open and hostile disrepute?

Or perhaps, to tweak the upturned noses of the smugly uncaring: when the time comes for Brexit — the before, during, and after; the social, political, and economic — to be incorporated into the secondary school curriculum, whom will you want to be calling the shots? The partisans on Twitter? The Tory government? I would prefer that it be the nationally accredited examination board; that they pursue objectivity; and that they ignore silly, exhibitionist tweets.

Second, AQA has just publicly endorsed a historical narrative. They can no longer claim to be teaching history as accurately, impartially, and objectively as possible, because they have just declared for one side of a debate. ‘But there is no debate here.’ Prove it: answer the question in the negative, more convincingly than your opposition. What’s that called again?

Accuracy, impartiality, and objectivity used to be primary goals of most academic endeavour; we retain these goals, but install above them a moral filter, apparently to be determined on a whim by the inexpert social media punter.

“It was deeply shocking to see how ingrained racial injustice is,” said Hannah to the BBC, going on, “[i]f this is how they're presenting the history of Native Americans with such bias my concern is whether that is a repeated pattern in the framing of US history and whether that is coming up throughout the course.”

The complainant references a bias inherent in the question, but she and her Twitter sycophants seem stunningly unaware of their own, very obvious bias: that it is so inconceivable that the treatment of Native Americans could have been exaggerated that the merely implicit suggestion is, to they the faint of heart, “horrifying” and “unacceptable”. So much so as to apply pressure for the offending question to be excised from the curriculum — which would be actioned without pause.

These ‘educators’ have quite clearly adopted a ‘correct’ reading of history — as if no historian were ever beholden to their own opinions; as if history were a set of incontrovertible facts painting a complete picture in monochrome; as if they alone have uncovered that picture, without error or bias, and can thus hamstring our children’s intellectual freedom in its infancy!

Third, and this does require emphasis because it is subtle and easily brushed aside if one does not consider the wider implications of AQA’s decision: this educational institution is abdicating its responsibility to foster open inquiry, critical thinking, and unbiased learning amongst our children. There are very, very few questions that cannot ethically be asked of the dominant narrative, and it is the duty of the educator to encourage and inspire those questions.

Undoubtedly, there have been failures in that regard over the years; I feel personally let-down by my late-’90s-to-early-’00s school curricula for not having been taught about the British empire and its attendant misdeeds, particularly in my mother’s native India.

The way to remedy these failures is not to fence-off spaces of inquiry that some few among us deem inappropriate for young minds. Perhaps my forebears thought the Jallianwala Bagh massacre inappropriate for my young mind? Whatever the reasoning, a study of the British Raj was absent from my education; sorely so, as many would now agree.

A biased narrative will never be truly expunged by blindly adopting its opposite; despite the colonialist reckoning that we seem to be living through, many or most remain ignorant of the actual history. The lazily naive operate under the delusion that colonialists were largely benevolent and magnanimous toward their subjects, bringing gifts of industry, technology, and infrastructure, whilst the aggressively self-righteous imagine little devil horns beneath every British helmet, perfectly harmonious and prosperous preconditions, and a seething hatred for the British in the hearts of every modern Indian.

Many of us fit into one of these two camps, and most would have benefited from a more expansive education; ought we not to insist upon a broadening of the educational landscape, to ask the difficult questions and shun the simple narratives, to study a broad range of sources, critically assessing each for their credibility?

Anyone’s gut reaction to the Native American question is along the lines of ‘no, the treatment of Native Americans has probably not been exaggerated’. But a historian is supposed to be more than just anyone, where history is concerned. Historians argue their cases on the merits of diverse, often contradictory pieces of historical evidence, and they are apt to disagree with one another in their conclusions — else the discipline would be pallid and undersubscribed.

This particular question is tinder for a passionate classroom discussion, one that might inspire kids to pursue history further. I would go so far as to say that it is a good question, precisely because it will force students to think critically about their own default opinions, and to evaluate oppositional ideas objectively. Are we to accept, on behalf of future generations, that the honing of such ever-relevant skills is less important than hammering home this narrative?

The complex interweaving of biased narratives over time, interacting with the changing culture at the moments of reflection, is the very meat of history. After grappling with historical materials under the tutelage of a competent teacher, should a thoughtful 16-18 year old student not be able to assess our current perception of the treatment of Native Americans, and the forces having shaped it, versus the historical record, versus the underlying reality? Is that not the point of this question, and of historical study more broadly? The kid is free to answer: ‘No exaggeration here’ — they need only articulate an argument. If Hannah’s students are unable to do so, whose fault is that?

Are we in the business of teaching students how to study history, or are we teaching students how to perceive history? Are the examiners demonstrating — retroactively, it should be said — their commitment to equity, diversity, and inclusion, or are they cowering before an anticipated Twitter storm?

Should a commitment to EDI have AQA bowing before a limp threat display from one mentor — who should teach something other than history if they wish to traffic only in the fair, the just, and the “acceptable” — and censoring tough questions from textbooks?

Why, exactly, does a commitment to EDI require that we not ask this question? According to Hannah, it is “quite problematic” (read: blasphemous). Why? Feelings, harm, inclusion, genocide, excuses, fairness, people, slavery, oppression, justification, disadvantage, violence, colonialism, white-washing, exclusion, disenfranchised, pride, subjugation, history — blah, blah, blah.

How can I be so dismissive? Because I know that there would be no issue, nor should there be, with the equivalent question:

To what extent do you believe that the treatment of Native Americans has been understated?

Phrase it this way, and the book stays. Why not just phrase it this way then? A better question is: why can we not phrase it the other way without a fucking news story? A good answer still requires the student to consider possible exaggerations. A good teacher should withhold marks from those who answer only ‘for’.

For the youth worker on Twitter, and for the spineless at AQA, the commitment is not to education, nor even to so-called EDI. It is to Newspeak, to doublethink; to willingly, shamelessly suspending our drive to critique; to demonstrating our allegiance to Big Brother, in the hope that future-history will look kindly upon us.

It will undoubtedly, artificially, look kindly upon us, if we find ourselves in Orwell’s 1984. If, on the other hand, we continue to value secular education, future-historians may look back at this as a flirtation with ideological corruption. I had naively hoped that this was a university phenomenon, and that the politicisation of minors’ learning was a mostly-American madness. Alas, the West is interconnected, and my optimism may have been misplaced.

When I studied history at GCSE level, my teachers were very clear that a coherent argument in answer to any proposition should visit both camps, ‘for’ and ‘against’. I also recall being required to take sides in debates that I did not want to take. If I wanted the grade, I had to steel-man the arguments that I would rather straw-man. It was difficult, but not altogether unpleasant, to inhabit the opposing point of view. My learning was improved as a result, despite the aforementioned gaps in the corpus.

I am not arguing ‘for’, or ‘against’, the notion that the treatment of Native Americans has been exaggerated. I argue for the student brave enough to take it on, to do so carefully, and with a nuanced reading of the historical record. To take the biases of the historians, the biases of the conquerors, and the biases of the conquered into account. To operate without needing to satisfy the petty opinions of their teachers, to demonstrate their research, rigour, and skill in crafting arguments for positions that they do, and do not, believe in.

Tragically for the youth of today, it would seem that their mentors prefer to take to Twitter in a moment of discomfort, to bring the threadbare mob down upon the craven exam boards and quivering publishers, to ensure that no young adult ever be asked a question that the teacher, or the preacher, already has an answer for.

To what extent do you believe the treatment of Native Americans has been exaggerated?

I-

NO, don’t try to answer that, Alex. The answer is not at all, and it is unacceptable to suggest otherwise.

Asking provocative questions does not identify one with distasteful answers, and all questions are provocative until they are not. We morally outlaw open inquiry at our own peril; if we fail to get off of this slippery slope, our children will soon be stupid. They will parrot the unsophisticated line, they will be unable to engage productively in debate, and they will shield themselves from the real, harsh world with moral indignation. Our children will pay for our cowardice.

Can we not delve deeply into our history, into the dark and grimy recesses of atrocity, whilst retaining our critical faculties, and challenging our preconceptions? I think we can — do not let Hannah and her ilk, the performance troupe, tell you that you, and your children, cannot.